"Venture capital money is money with a price tag. The moment a company receives investment, it assumes the obligation to rapidly grow and exit investors at a high multiple."

Seo Kwang-yeol, CEO of Codebox, has raised over 23 billion won in cumulative investment and experienced the company's acquisition by Dunamu. Despite this, he says, "If I were to start a business again, I'd want to create a company that could survive without investment." As a founder who grew through investment, he understands the structural weight of that choice.

Having closely observed the operations of over 11,000 corporations over nine years, he believes that the key to a startup's success or failure isn't its idea, but rather "the difference in perception of operations." He argues that the quality of a corporation's operations directly determines its access to capital markets, and this gap only widens over time.

CEO Seo Kwang-yeol, a computer engineering major and lifelong developer, began his journey with the realization that the entire startup process—from founding and operating to raising capital—was "excessively outdated." He saw the problem as a system in which core corporate decisions—such as incorporation, registration and resolutions, stock compensation, and investment attraction—were dispersed across Excel, documents, messengers, and email, making it a given.

“It felt like an area that hadn't been improved upon for decades because it was 'just the way it was', even though technically it could have been done in a much more transparent and automated way.”

The question he repeatedly asks entrepreneurs is simple:

“What problem exactly am I solving right now?”

He argues that whenever a new technology emerges, instead of immediately thinking about what it can do, we should first consider what problems are currently unsolved in the market. He argues that focusing on speed and perfection when the problem definition is unclear can easily lead to a loss of direction.

"Operations aren't an afterthought…the most important moment is the most expensive."

From its inception, Codebox chose the heavy lifting of corporate operations, shareholder management, and investment infrastructure. The reason for choosing this market over a fast-paced consumer service was clear.

"Contrary to the perception that this area is difficult and complex, I believe it's a core area that every corporation must prioritize for growth. As a company grows, governance, shareholder management, investment history, and decision-making consistency become essential, not optional."

The moment startups put off corporate operations as a "later issue" and incur the greatest costs is usually when the company's value is fully assessed. During investment rounds, mergers and acquisitions, or IPOs, when external stakeholders scrutinize the company's internal affairs, accumulated operational vulnerabilities are suddenly exposed. Structures and records that normally appear to be flawless can actually pose real risks, delaying decision-making or worsening conditions when faced with a critical transaction.

CEO Seo Kwang-yeol personally experienced the weight of investment contract provisions when he worked as CTO at a previous startup.

"There was a clause that effectively restricted the co-founders from leaving the company, as they were tied to the company as stakeholders. When it became necessary to leave, this clause became a real shackle, and I was only able to leave after returning all my shares. That experience taught me that the corporation and its stocks aren't something you can just sort out later."

The same holds true for stock compensation. Stock options may seem like a distant future story when granted, but when they're actually exercised, the accumulated problems suddenly become a reality. It's not uncommon to discover belatedly that a past resolution was legally flawed, only to find a solution later. The costs of this go beyond mere administrative overhead; they can lead to a breakdown in trust and ruptures in relationships.

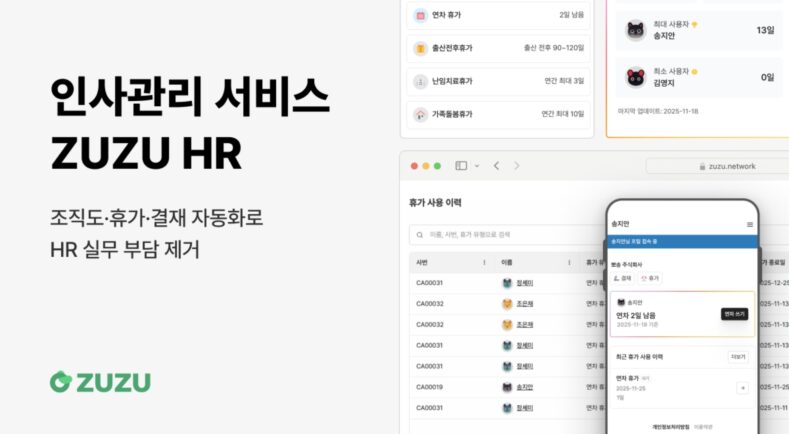

"This is why ZUZU has integrated all of its corporate operations into a single infrastructure. This isn't simply a choice to make things easier; it serves as the minimum foundation for companies to maintain their negotiating power and choice at every critical moment."

The Power Law of Venture Capital Investment… "Not Every Business Can Draw a J-Curve"

CEO Seo Kwang-yeol has repeatedly emphasized the structural nature of investment attraction through numerous articles and interviews. The most common problem entrepreneurs encounter when misunderstanding investors' expected returns and fund structures is a lack of understanding of the growth curve their business is expected to follow when accepting capital.

"The return structure of venture capital fundamentally follows a power law. Many companies invested in by a single fund fail or achieve limited results, while a very small number of companies must generate returns of 100 times or more for the entire fund to survive."

In this structure, venture capitalists aren't looking for "stable, good companies." They're looking for a small number of outliers capable of driving the entire fund's profits. As a result, startups that receive venture funding, whether intentionally or not, are forced onto a J-curve path of rapid growth. A strategy of rapidly dominating the market and achieving nonlinear growth becomes a prerequisite.

The problem is that not all businesses can achieve this growth curve. Therefore, CEO Seo argues that venture capital isn't always the answer. He argues that for businesses where power-law growth is difficult due to the nature of the market and technology, investment can actually be detrimental. Attracting investment isn't simply about raising funds; it's about tying yourself to a specific growth function.

"Market size, customer purchasing cycles, and the scalability of technology often don't allow for rapid growth. Nevertheless, receiving venture capital often leads to repeated decisions that accelerate growth, regardless of the nature of the business. Typical examples include reckless expansion into unproven markets, excessive upfront expansion of organizational and cost structures, and pursuing growth metrics that don't align with long-term profitability."

11,000 clients have proven that "operating quality determines access to capital markets."

ZUZU has over 11,000 clients. These include virtually all types of corporations, including startups, small and medium-sized enterprises, and unlisted corporations. The problem CEO Seo Kwang-yeol experienced on the ground was not a lack of ideas, but a gap in operational awareness.

"The fact that many of ZUZU's early clients were startups may actually be proof that startups have a higher level of operational awareness than traditional businesses. Because startups inherently start with a prerequisite of investment, shareholders, and growth, they tend to view corporate operations as a systemic issue to be managed now, rather than something to be resolved later."

On the other hand, general companies often fail to appreciate the importance of corporate governance until they encounter capital markets. Since they don't anticipate external investment, mergers and acquisitions, or equity transactions, they have little incentive to meticulously manage shareholder management or governance structures to meet capital market standards. However, once they encounter capital markets—through bank loans, venture capital investments, or private equity acquisitions—the operational gaps that have been neglected quickly become costs.

The most structural misconception that CEO Seo Kwang-yeol repeatedly encounters in the field is the perception that operations are simply administrative work and that growth comes first.

"In reality, the level of operational excellence determines the level of access to capital markets. ZUZU is not simply a tool that provides operational convenience; it aims to be an infrastructure that naturally helps businesses reach the minimum operational standards required by capital markets."

"Investment is conditional capital… If I were to start a business again, I would create a company that would survive without investment."

CEO Seo Kwang-yeol views venture capital investment as conditional capital. "Venture capital isn't just cash; it's money with a price tag attached. The moment a company receives even a single investment, it assumes the obligation to rapidly grow and deliver a high multiple exit to its investors."

The reality of this label is heavier than you think.

Capital inevitably carries obligations, and those obligations are specified in shareholder agreements. Investors not only participate in key corporate decisions, but in some cases, even exert significant influence over the founder's exercise of property rights. Attracting investment isn't simply about receiving money; it's about sharing in the company's control structure.

So he speaks honestly.

"Although Codebox has received over 23 billion won in cumulative investment and was even acquired by Dunamu, if given the opportunity to start a business again, I'd love to create a company that could sustain itself without investment and grow at my own pace."

There is one most important criterion when deciding whether or not to receive an investment.

"The question is whether you can handle the pace of growth investors demand. If that pace aligns with your business's market, technology, and organizational readiness, the investment will undoubtedly give you wings. However, if that pace doesn't match, the investment could actually be a cause of your downfall."

ZUZU runs events like the "Investment Insight Club" to help companies properly understand the structure and nature of investment attraction. By transparently sharing investor perspectives, fund structures, and growth expectations, our primary goal is to empower CEOs to determine not whether they should receive investment, but rather what investment conditions are right for them.

CEO Seo Kwang-yeol singled out one question that early-stage entrepreneurs should ask themselves: "What problem exactly am I solving?"

"In the field, whenever a new technology emerges, expectations about what it can do often overwhelm. This naturally leads to developing the technology first, then moving on to identifying the problem. However, solutions that struggle to find the right solution often struggle to gain acceptance in the market. Conversely, teams that diligently consider market issues, pinpoint their root causes, and then propose solutions that address them often generate a clear response, even initially. This is because their clarity in problem definition precedes speed or completeness."

Even now, nine years into his business, CEO Seo Kwang-yeol asks himself the same question every day: "What problem am I solving right now? If I can clearly answer this question, the direction for the next step will naturally begin to emerge."

The question that Seo Kwang-yeol, CEO of Codebox, repeatedly asks entrepreneurs is not about technology or speed, but about defining the problem.

“What problem exactly am I solving?”

If you can answer this question clearly, whether you take investment or not, whether you go fast or slow, the direction will begin to appear natural.

You must be logged in to post a comment.